- About▼

- Exo 101▼

- News

- Research▼

- Jobs + Internships▼

- Current Opportunities

- B.Sc. Summer Internships

- Graduate Studies

- Lumbroso Grant for Ambassadors

- Jean-Marc Lauzon Grants

- Postdoctoral Fellowships

- Maunakea Graduate School

- Secondary School + Cegep Internships

- Astrophysics Discovery Moments (Moments découverte en astrophysique)

- The Eclipse Ambassadors Training Program

- Public Outreach▼

- Our Events

- Astronomy on Tap

- Les Grandes conférences de l’iREx

- AstroMIL: an astronomy celebration for all!

- Podcast – Les astrophysiciennes

- ExoBites Video Series

- La petite école de l’espace

- Cosmic Club

- Exoplanets in the Classroom

- Beyond the Stars: Exploring Space, Rooted in Place

- Eclipse

- Invite an astronomer

- iREx in the Media (in our Reports)

- Social Media

- Newsletter

- Our Team▼

- Contact Us

- FR▼

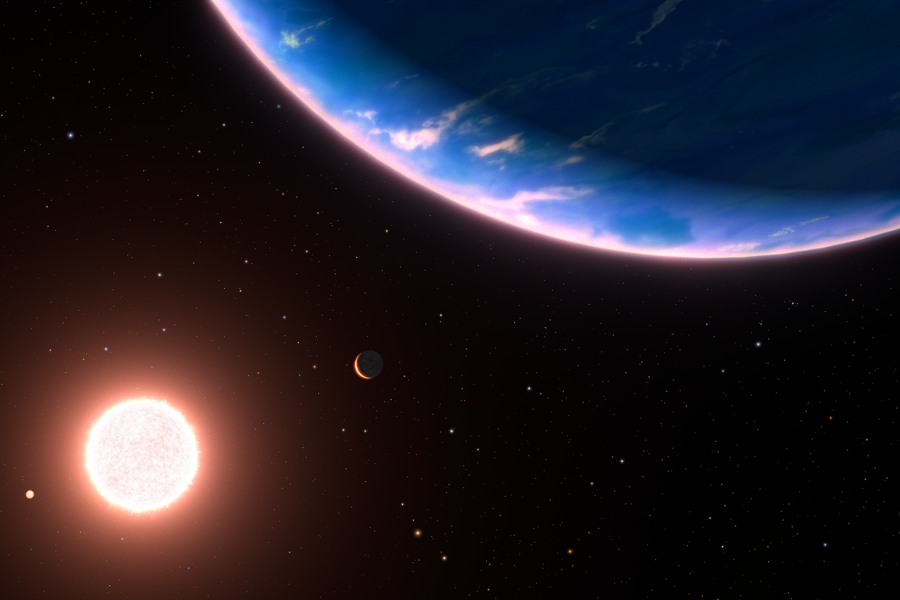

Headed by scientists at Université de Montréal, the study was

Headed by scientists at Université de Montréal, the study was  “Our observing program was designed specifically with the goal to not only detect the molecules in the planet’s atmosphere, but to actually look specifically for water vapour,” said the study’s lead author,

“Our observing program was designed specifically with the goal to not only detect the molecules in the planet’s atmosphere, but to actually look specifically for water vapour,” said the study’s lead author,